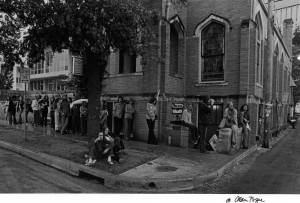

Georgia Armstrong remembers standing in a long line wrapped outside an elementary school one Sunday morning as a child. She was waiting to receive the new polio vaccine. It came delivered on a sugar cube.

“[Back then] kids were getting polio like crazy, I mean people were keeping their kids home from school, didn’t let them go swimming,” she says from her office at People’s Community Clinic. “And then the vaccine came out and everything changed.”

Armstrong, R.N., oversees the clinic’s Immunization Program, which controls the clinic’s inventory of Advisory Committee of Immunization Practices (ACIP) vaccines and monitors when PCC patients are due for a dose. In 2013, 17,157 immunizations administered last year, the majority to children under age 5.

“We have a strong program,” Armstrong says. “We have all the vaccines that are recommended for everybody. “We just want to make it our standard of care for best practices to prevent what’s preventable.”

Armstrong, immunizations staff, and volunteers, have streamlined the tracking system that alerts PCC providers when patients are due to receive vaccinations. Although the City of Austin does not have a compliance system in place, PCC strives to exceed national compliance rates for youth and adult patients. Adult patients requires a bit more finesse than younger patients because they do not follow a vaccination schedule dictated by age.

“It’s also disease and health indications of when they would need a certain vaccine or not,” Armstrong says. “That just takes some time, but we’ll get it figured out.”

The walls of the adult exam are decorated with posters of individuals blistered with shingles, an infection caused by the chickenpox virus that commonly affects patients over age 60 and those with suppressed immune systems. Armstrong launched a PR campaign to get more adults eligible for the shingles vaccine to get it and avoid what could potentially be years of pain. Beside her desk hums one of six refrigerators containing vaccinations. Fastened to the front is a clip from the Austin-American Statesman about last year’s flu season. She makes sure to stay on top of flu vaccinations for PCC staff too.

“I like the whole prevention idea,” Armstrong says after fastening a Band-Aid on her interviewer. “Sometimes you realize that you spend a lot of time [working] with health education and then [patients] leave the clinic, light up their cigarette and drive through Popeye’s and buy some fried chicken. But when you administer a vaccine you know you’ve done it – you’ve put protection in ‘em right there. You go … next! And that appealed to me.”

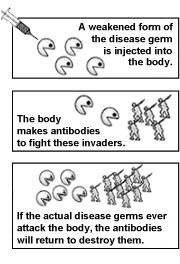

Armstrong recalls elementary school classmates who came down with polio. As a nursing student in the 1970s she became friends with a woman was one of the longest polio victims to live with the assistance of an iron lung. She encountered a child that had to be tube fed because of brain damage he sustained from a haemophilus influenza type B (HIB) infection.

“It was just awful. He was like a vegetable,” Armstrong says shaking her head. “Vaccines can prevent that type of thing. It’s incredible what we have. People say, ‘Don’t stick my baby so many times!’ I say ‘Hallelujah there’s that many sticks. More sticks means more protection … Vaccines are just miracle drugs, they really are.”

Her tenure at PCC began in 1993 as an employee of the state’s Shots for Tots program, which she ran out of the clinic once a week. Armstrong was hired on at PCC a year later to run its walk-in clinic. At the time, the clinic did not have a vigorous pediatric department.

“If there were five Well Child Checks in a week’s time it was kind of amazing,” she says. “Things have changed a lot.”

The clinic now has a robust pediatric department and four times as many employees. Over the years Armstrong has noted changes in the mindset of community members—namely, those who are electing not to vaccinate their children from diseases that have largely disappeared from the United States. This decision reduces the community’s herd immunity, leaving individuals who haven’t been vaccinated due to age, allergy, or illness vulnerable. That’s why Armstrong is vigilant about vaccination.

“Some kids can’t get vaccinated,” she says. “Some kids may have a very suppressed immune system so even if they are vaccinated, it doesn’t produce the antibodies needed to protect them from the disease. It’s not just about you, it’s about everybody you’re around.”

Last year an outbreak of the measles occurred in the Fort Worth and this summer in Austin, a Hepatitis A scare arose. Pertussis, also known as whooping cough, is making a comeback in Texas as well as in California. Some parents still question whether or not the MMR vaccine causes autism after a 1998 paper by Andrew Wakefield linked the two. It has been proven to be false many times since, but doubt lingers. Armstrong sees her role as an educator who can point people with questions to reputable sources and help them make more informed decisions about vaccinations. She wants them to be afraid of the things they should be afraid of: preventable diseases.

“We have to figure out how to make them unafraid,” she says. “I think some parents also aren’t familiar with the diseases. They haven’t seen them in their lifetime and so they’re more afraid of the vaccine than they are the disease. They don’t really understand the risk-benefit ratio, whereas, someone older like myself … I personally have four friends that have polio because the vaccine wasn’t available. They don’t remember that that’s exactly how it was when I was little with polio … People should be in line to get these vaccines.”

-KM